Chronic Pain and PTSD

Chronic Pain and PTSD

When people experience both chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), each condition can exacerbate the other. This article provides information and options to providers working with people who have both PTSD and chronic pain.

In This Article

What is chronic pain?

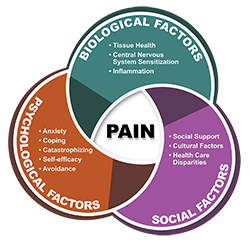

Chronic pain is a common issue that affects 1 in 5 Americans (1) and affects more Veterans than non-Veterans (2). Whereas acute pain comes on quickly after an injury and lasts a short time, chronic pain lasts longer than expected for a given injury, or more than 3 to 6 months.  Acute pain signals that an injury exists and there is a need for rest, healing, treatment, or recovery; but chronic pain lasts beyond the recovery time (in the case of an injury) or may have an unknown cause and does not necessarily signal that there is tissue damage. Chronic pain is not a simple indicator of ongoing tissue damage but is instead a complex biopsychosocial condition.

Acute pain signals that an injury exists and there is a need for rest, healing, treatment, or recovery; but chronic pain lasts beyond the recovery time (in the case of an injury) or may have an unknown cause and does not necessarily signal that there is tissue damage. Chronic pain is not a simple indicator of ongoing tissue damage but is instead a complex biopsychosocial condition.

Because pain is influenced by social and psychological factors, individual differences and health care disparities have been identified in both the experience and the care of pain (3,4). For instance, chronic pain is more prevalent among women than men, the impact of chronic pain is greater among racial or ethnic minorities, and lower socioeconomic status is related to higher pain prevalence and severity (3).

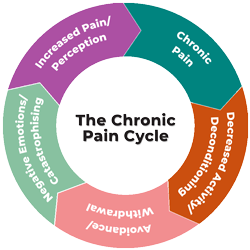

Understandably, a person in chronic pain often assumes that their pain is a signal of potential harm or damage and will thus want to rest or avoid movements that may trigger that pain. Unfortunately, this can lead to a vicious cycle of decreased activity leading to physical deconditioning, which makes further activity more aversive, and can also lead to withdrawal from positive life experiences. Chronic pain often involves central nervous system sensitization, meaning that the nervous system has developed a decreased threshold for pain and threat perception, resulting in pain in the absence of ongoing tissue damage. However, since human beings reflexively interpret pain as an indicator of tissue damage, concern about such damage may result in pain-related anxiety and catastrophizing, which in turn can amplify the overall pain experience (5). It can be challenging for providers to communicate to patients that their pain is both real, mediated by the brain's perception of threat of injury, and does not necessarily indicate tissue damage. A process such as neuroscience education can help providers to do so with validation and empathy while still helping patients to understand their pain in a new and more workable way (6).

Unfortunately, this can lead to a vicious cycle of decreased activity leading to physical deconditioning, which makes further activity more aversive, and can also lead to withdrawal from positive life experiences. Chronic pain often involves central nervous system sensitization, meaning that the nervous system has developed a decreased threshold for pain and threat perception, resulting in pain in the absence of ongoing tissue damage. However, since human beings reflexively interpret pain as an indicator of tissue damage, concern about such damage may result in pain-related anxiety and catastrophizing, which in turn can amplify the overall pain experience (5). It can be challenging for providers to communicate to patients that their pain is both real, mediated by the brain's perception of threat of injury, and does not necessarily indicate tissue damage. A process such as neuroscience education can help providers to do so with validation and empathy while still helping patients to understand their pain in a new and more workable way (6).

Chronic Pain and PTSD Frequently Co-occur

Two reviews found that people with chronic pain have elevated rates of PTSD, especially among clinical populations and among those with specific subtypes of chronic pain including chronic pelvic pain and chronic widespread pain (7,8). Certain types of trauma may be associated with certain types of pain—for instance, abuse has been linked to chronic pelvic pain in women—but this association is rarely straightforward (9). For this reason, personalized assessment and an approach that recognizes the potential of prior trauma can be helpful for any pain presentation.

Veterans with chronic pain may also have high rates of PTSD (7). Compared to Veterans with chronic pain and no PTSD, Veterans with chronic pain and comorbid PTSD had more pain, disability, depression, sleep disturbance, health care utilization, catastrophizing beliefs and lower pain self-efficacy (10). They are also more likely to be prescribed opioids and to engage in suicide-related behavior (10).

Why might PTSD and chronic pain co-occur?

When a single event such as a motor vehicle crash leads to both chronic pain and PTSD, then pain itself may be a trauma reminder. But even when pain is not linked to the index trauma event, the feeling of being in pain or feeling like their own body is out of their control may be a reminder of trauma for some Veterans. At other times, the connection between pain and PTSD may not be obvious; there is some evidence that a variety of stressful childhood events predispose to developing both chronic pain and PTSD in adulthood (11,12).

There are several models that have been developed to try to explain why chronic pain and PTSD may be linked (see our PTSD Research Quarterly (PDF) on this topic for an overview of each model). In general, these models indicate that some factors predispose people to both chronic pain and PTSD (e.g., anxiety sensitivity, childhood adversity) or can amplify the effects of each (e.g., heightened attention to and avoidance of generally threatening or painful stimuli). The hypervigilance and arousal that characterize PTSD may contribute to dysregulated stress responses, which in turn lead to central sensitization. Indeed, a meta-analysis found that a range of trauma experiences and/or PTSD is associated with increased pain detection and central sensitization (13).

Clinically, this can mean that those with both chronic pain and PTSD are more attentive to signs of anxiety or pain. They may also be more likely to catastrophize, showing concern that anxiety or pain indicate significant problems. (For instance, "This pain means something is really wrong with me," or "This intrusive thought means that I can't hold it together.") In turn, catastrophizing amplifies the existing symptoms and makes people want to avoid any reminder of either pain or anxiety. In PTSD, this can take the form of avoidance and hypervigilance to trauma cues, whereas in chronic pain it can look like either avoidance of physical activity or "boom-bust" cycles of physical activity (too much followed by too little). These combined types of avoidance can lead to isolation, physical deconditioning, and low quality of life, all of which contribute to low mood and further hesitance to behaviorally engage. Poor sleep and generally poor coping likely also contribute to the lower levels of functioning in those with comorbid PTSD and chronic pain (10,14,15). Although the whole cycle of PTSD and chronic pain is quite understandable and even initially functional from the standpoint of self-protection, it is psychologically and functionally detrimental and increasingly maladaptive in the long term.

What does effective treatment look like for a person with PTSD and chronic pain?

PTSD and chronic pain can exacerbate each other, and each can make treatment of the other more challenging. An initial inter-disciplinary evaluation is helpful to assess for both medical and psychiatric problems along with psychological processes that may contribute to both pain and PTSD (e.g., catastrophizing, anxiety sensitivity). Given the somewhat higher comorbidity rates, an evaluation should include assessment for depression, substance use (both prescribed and non-prescribed), and suicidal ideation. If an opioid abuse disorder is present, that may warrant treatment prioritization (see below).

Continuing Education Course

Treating Co-occurring Chronic Pain and PTSD

This PTSD 101 online course identifies best practices for treating those with PTSD and chronic pain.

Chronic pain and PTSD may have been under-recognized, under-treated, or inadequately treated among racial minorities, those in rural settings, and older persons (4,16). As such, good clinical care may entail active efforts to engage patients from historically marginalized groups, drawing attention to any implicit biases toward these groups, and offering standardized, interdisciplinary assessments to all patients.

Pain treatment

Because medical interventions are not always able to fully resolve chronic pain, the goal of chronic pain treatment is more about improving functioning and quality of life than about eliminating chronic pain. The mental shift from eliminating pain to living well with it (and from pain as damage to pain as noise) can be very challenging for patients. Coming to terms with chronic pain can involve anger, sadness, feelings of helplessness, or lack of control. Providers can help with buy-in and reducing stigma by educating patients that their physical pain can have a biological contribution (i.e., central sensitization) that can be amplified by psychological phenomena (e.g., trauma) and dampened by a psychological intervention (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, 5,10). This can reduce the sense that providers are not taking their pain seriously. Providers can also be honest about the limitations of medical science in being able to resolve chronic pain and empathize with patients around their frustration with this reality. Along with psychoeducation, restoring some sense of control and empowerment can also be an important aspect of treatment.

Successful chronic pain treatment often necessitates a customized, multi-modal approach to address physical, emotional and social needs, with patients taking an active role. Pain treatment may incorporate talk therapies, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, and medication, for instance.

Specific talk therapies have good evidence for their efficacy in managing chronic pain (17).

- CBT for Chronic Pain (CBT-CP) has the most research support and is widely available within VA. It involves training in modifying pain catastrophizing along with increasing paced activity, relaxation, and pleasant activities. The goals are to decrease avoidance and overall to engage in meaningful activities again so that pain is not as bothersome.

- ACT for Chronic Pain also has some initial empirical support (18). It helps patients to engage in valued activities in the presence of ongoing aversive internal experiences (i.e., pain, difficult thoughts, sadness, anger, etc.) which can result in improved mood, functioning, and quality of life.

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based CBT help patients bring a non-judgmental attitude toward negative thoughts and sensations. This perspective can then be leveraged to engage in meaningful activities even when pain and distress may be present.

PTSD treatment

The most effective treatments are trauma-focused psychotherapies and certain antidepressant medications.

Combining Treatment for PTSD and Chronic Pain

One question is how to best combine treatments for PTSD and chronic pain (19). They can be treated sequentially, in parallel, or in an integrated fashion.

By default, if patients see different providers for PTSD and chronic pain, then sequential treatment may be most common. Which condition to start with can depend largely on patient preference and on severity of each condition. In some cases, treatment of pain may have less stigma, and successful treatment could make patients more open to subsequent PTSD treatment (there is even some preliminary evidence that comprehensive pain treatment without a trauma focus can have some positive effect on PTSD via improvement in pain catastrophizing; 20, and that trauma-focused psychotherapy alone can improve pain-related functioning [21]). A concern with this model is that the untreated condition may interfere with successful treatment of the other.

Treating PTSD and pain in parallel (with 2 different providers at the same time) may expedite treatment gains; ideally improvements in one condition also help lead to improvements in the other, leading to a positive upward spiral. The downsides are patients feeling overwhelmed, along with the potential for providers to collaborate poorly or have conflicting philosophies. For instance, if a PTSD provider is not fluent in pain treatment and encourages a patient not to increase movement due to pain, this may undermine pain treatment or confuse the patient. Likewise, pain providers may unwittingly encourage accommodation of PTSD avoidance symptoms. Therefore, if integrated treatment is not possible, at a minimum it can be helpful to have communication between providers to ensure that patients are getting consistent messages from each provider.

An integrated PTSD-chronic pain treatment model is rare but may theoretically be optimal in terms of less burden on patients, providers, and the system. Further, in an integrated model providers can best help patients understand how PTSD and chronic pain exacerbate each other, potentially increasing motivation for both treatments. In this model a provider or multiple providers treat both conditions and intentionally collaborate. For instance, some of the trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies share a goal with CBT-CP of decreasing avoidance of feared or aversive stimuli. This compatible underlying philosophy, combined with validation of the fact that avoidance makes intuitive sense but ultimately can lead to a more restricted life, may lend themselves to combined treatments. One pilot study, for instance, tested a 12-session integrated treatment using elements of Cognitive Processing Therapy and CBT-CP (22), and another tested a 6-session massed version of the same treatment (23). Several other studies have tested pilot integrated approaches as well (19), but there is no available manual or large-scale empirical evidence for these approaches yet.

There is currently no research evidence to promote one of the above options over another. Regardless of the model chosen, effective treatments are likely to involve coordination among treatment team members so that patients receive consistent messages about both chronic pain and PTSD from their providers.

Key Points About Medication-based Pain Treatment

Treatment of chronic pain has changed considerably in the past 30 years. Beginning in the 1990s, the number of prescriptions for opioids began to increase in the U.S. It was thought that opioids were a useful and compassionate way to treat chronic pain, and that the risk of addiction and overdose was outweighed by the benefits of pain relief. But as opioid use gradually increased, risks of their use became clearer. First opioids do not cure pain, and tolerance can lead to increasing use (especially problematic for those with a history of substance misuse). Most strikingly, opioid overdose deaths increased steadily over time.

Research has started to highlight why opioids have been so problematic. A large randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that people taking opioid medications had more side effects and no better pain relief than people taking nonopioids (24). Moreover, developing research suggests that for some people with chronic use or misuse of opioids, there is a risk of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, in which pain is experienced at higher levels (or lower thresholds) than prior to taking the opioid (25,26).

One other potential danger is among patients who are prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines. When taken together, benzodiazepines and opioids can result in slowed breathing, decreased oxygen intake, slowed reaction time, accidental overdose, pregnancy risks and even death. Although contra-indicated for PTSD, benzodiazepines are among the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications in the USA (27). Moreover, a large study of Veterans found that those with comorbid PTSD and chronic pain were more likely than either group alone to be prescribed both benzodiazepines and opioids (28). There is also some indication that women Veterans are more likely to be prescribed medications such as benzodiazepines which are recommended against in clinical practice guidelines (29). Learn more about the use of benzodiazepines for PTSD in Veterans Affairs.

Because of the increasing evidence of risk, the CDC issued guidelines in 2016 that called attention to safety concerns of using opioids (especially concurrently with benzodiazepines). The guidelines recommended using a variety of modalities to address pain instead of relying on opioid pain medication. Thus, if patients are on a combination of opioids and benzodiazepines, it is appropriate for providers to prioritize discussing with patients decreasing or tapering off one or both of them. However, for patients who have taken these medications long-term, withdrawal can be associated with significant physical and mental distress. For instance, withdrawal can sometimes lead to rebound anxiety or pain (27). If these medications have been used to cope with PTSD symptoms, then decreasing or discontinuing them can be particularly difficult, because PTSD symptoms may also increase. For these reasons, the FDA noted in 2019 that such withdrawal must be managed with care and sensitivity, not done abruptly (or for populations for which opioids may be appropriate e.g., cancer; 30). Treatment can involve detoxification, medication-assisted treatments (e.g., buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone), or psychosocial treatment, depending on severity. And treatment for PTSD (at the very least to help develop other, safer coping mechanisms) will be a helpful part of treatment in these cases.

Summary

Chronic pain and PTSD can exacerbate each other, contributing to poor quality of life. Coordination among treatment care members can promote consistent messages about PTSD and chronic pain management. Good quality care will integrate treatment of the co-occurring conditions to help empower patients so that pain and anxiety do not stop them from meaningful engagement in their life.

Resources for Providers:

- VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pain

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain Among Veterans: Therapist Manual (PDF)

- CDC's Opioid Overdose Information for Health Care Providers

Resources for Clients:

- VHA Pain Management Tools for Veterans and the Public

- CDC's Opioid Overdose Information for Patients

References

- Yong, R. J., Mullins, P. M., & Bhattacharyya, N. (2022). Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain, 163(2), e328-e332. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291

- Nahin, R. L. (2017). Severe pain in Veterans: The effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. The Journal of Pain, 18(3), 247-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.021

- Fillingim, R. B. (2017). Individual differences in pain: Understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain, 158(Suppl 1), S11-S18. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000775

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United States, 2022. MMWR Recommendations and Reports (No. RR-3), 1-95. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Benedict, T. M., Nitz, A. J., Abt, J. P., & Louw, A. (2021). Development of a pain neuroscience education program for post-traumatic stress disorder and pain. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 37(4), 473-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2019.1633717

- Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. S., & Puentedura, E. J. (2011). The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(12), 2041-2056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.198

- Fishbain, D. A., Pulikal, A., Lewis, J. E., & Gao, J. (2017). Chronic pain types differ in their reported prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and there is consistent evidence that chronic pain is associated with PTSD: An evidence-based structured systematic review. Pain Medicine, 18(4), 711-735. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw065

- Siqveland, J., Hussain, A., Lindstrøm, J. C., Ruud, T., & Hauff, E. (2017). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with chronic pain: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00164

- Lamvu, G., Carrillo, J., Ouyang, C., & Rapkin, A. (2021). Chronic pelvic pain in women: A review. JAMA, 325(23), 2381-2391. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.2631

- Benedict, T. M., Keenan, P. G., Nitz, A. J., & Moeller-Bertram, T. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms contribute to worse pain and health outcomes in Veterans with PTSD compared to those without: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Military Medicine, 185(9-10), e1481-e1491. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa052

- You, D. S., & Meagher, M. W. (2016). Childhood adversity and pain sensitization. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(9), 1084-1093. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000399

- Raphael, K. G., & Widom, C. S. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder moderates the relation between documented childhood victimization and pain 30 years later. Pain, 152(1), 163-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.014

- Nanavaty, N., Thompson, C. G., Meagher, M. W., McCord, C., & Mathur, V. A. (2023). Traumatic life experience and pain sensitization: Meta-analysis of laboratory findings. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 39(1), 15-28. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000001082

- Alschuler, K. N., & Otis, J. D. (2012). Coping strategies and beliefs about pain in Veterans with comorbid chronic pain and significant levels of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. European Journal of Pain,16(2), 312-319. https://doi.org/10/1016/j.ejpain.2011.06.010

- Powell, M. A., Corbo, V., Fonda, J. R., Otis, J. D., Milberg, W. P., & McGlinchey, R. E. (2015). Sleep quality and reexperiencing symptoms of PTSD are associated with current pain in U.S. OEF/ OIF/OND Veterans with and without mTBIs. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(4), 322-329. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22027

- Spoont, M., & McClendon, J. (2020). Racial and ethnic disparities in PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly, 31(4), ISSN: 1050-1835. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V31N4.pdf

- Majeed, M. H., Ali, A. A., & Sudak, D. M. (2019). Psychotherapeutic interventions for chronic pain: Evidence, rationale, and advantages. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 54(2), 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217418791447

- Hughes, L. S., Clark, J., Colclough, J. A., Dale, E., & McMillan, D. (2017). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 33(6), 552-568. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425

- Murphy, J. L., Driscoll, M. A., Odom, A. S., & Hadlandsmyth, K. (2022). Posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. PTSD Research Quarterly, 33(2), ISSN: 1050-1835. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V33N2.pdf

- Gilliam, W. P., Schumann, M. E., Craner, J. R., Cunningham, J. L., Morrison, E. J., Seibel, S., Sawchuk, C., & Sperry, J. A. (2020). Examining the effectiveness of pain rehabilitation on chronic pain and post-traumatic symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 43(6), 956-967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-020-00160-3

- Shipherd, J. C., Beck, J. G., Hamblen, J. L., Lackner, J. M., & Freeman, J. B. (2003). A preliminary examination of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in chronic pain patients: A case study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 451-457. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025754310462

- Otis, J. D., Keane, T. M., Kerns, R. D., Monson, C., & Scioli, E. (2009). The development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Medicine, 10(7), 1300-1311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00715.x

- Otis, J. D., Comer, J. S., Keane, T. M., Checko (Scioli), E., & Pincus, D. B. (2024). Intensive treatment of chronic pain and PTSD: The PATRIOT Program. Behavioral Sciences, 14: 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11111103

- Krebs, E. E., Gravely, A., Nugent, S., Jensen, A. C., DeRonne, B., Goldsmith, E. S., Kroenke, K., Bair, M. J., & Noorbaloochi, S. (2018). Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: The SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 319(9), 872-882. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0899

- Higgins, C., Smith, B. H., & Matthews, K. (2019). Evidence of opioid-induced hyperalgesia in clinical populations after chronic opioid exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Anesthesia, 122(6), e114-e126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.019

- Lee, M., Silverman, S. M., Hansen, H., Patel, V. B., & Manchikanti, L. (2011). A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician, 14(2), 145-161. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2011/14/145

- Ait-Daoud, N., Hamby, A. S., Sharma, S., & Blevins, D. (2018). A review of alprazolam use, misuse, and withdrawal. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 12(1), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000350

- Outcalt, S.D., et al. (2014). Health care utilization among Veterans with pain and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Pain Medicine, 15(11), 1872-1879. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12045

- Hadlandsmyth, K., Bernardy, N. C., & Lund, B. C. (2022). Gender differences in medication prescribing patterns for Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A 10â€year followâ€up study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(6), 1586-1597. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22861

- Dowell, D., Haegerich, T., & Chou, R. (2019). No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(24), 2285-2287. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1904190

You May Also Be Interested In

Continuing Education Online Courses

Learn from expert researchers and earn free Continuing Education (CE) credits.