PTSD: National Center for PTSD

Trauma, Discrimination and PTSD Among LGBTQ+ People

Trauma, Discrimination and PTSD Among LGBTQ+ People

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses LGBTQ+ to refer to people with diverse gender and sexual identities. The LGBTQ+ acronym represents individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer. The "+" indicates any other minoritized identities such as intersex, asexual, pansexual or nonbinary. This article focuses on describing the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ people who have experienced trauma, discrimination and PTSD.

LGBTQ+ People Experience a Range of Stressors

Assault

Lesbian, gay and bisexual identities have been associated with higher victimization across the lifespan compared to those with a heterosexual identity, including experiences of child abuse and sexual and physical assault (1). In fact, LGBTQ+ individuals are nearly 4 times more likely to experience violent assault (rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated or simple assault) than their cisgender (i.e., person whose gender identity is the same as their sex as assigned at birth), heterosexual counterparts (2). As a result, LGBTQ+ people are at higher risk of developing PTSD, with prevalence estimates of up to 48% of LGB individuals and 42% of transgender and gender diverse individuals meeting criteria for PTSD (3). These estimates are much higher than the general population prevalence (4.7%; 4).

Minority stressors

LGBTQ+ people also experience various socially-produced stressors due to their identities—these are often referred to in the research as minority stressors. Minority stressors include external or distal experiences, such as discrimination and violent victimization, as well as internal or proximal experiences such as internalized stigma (shame), expectations or fears of rejection, and identity concealment (5,6).

Distal/External Experiences: Nearly half (48%) of transgender people report interpersonal discrimination, such as being verbally harassed or physically assaulted due to their identity in the past year (7). Furthermore, LGBTQ+ people face structural discrimination at local, state and federal levels (e.g., laws and policies that offer less protection to LGBTQ+ people) and across institutions such as education, employment, religion, housing and health care. For example, LGBTQ+ people can currently be evicted, denied housing, or denied entry to businesses in over twenty states. Only since 2011 have lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals been allowed to serve openly in the military. For transgender and gender diverse people, relevant policies have changed over time, with bans on military service being predominant.

The history of mental health care is especially problematic, given the inclusion of aspects of sexual identity and orientation in psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., "high risk homosexual behavior" in the ICD10; homosexuality as psychiatric diagnosis until 1973). Additionally, mental health providers have been positioned as gatekeepers of life-saving gender affirming medical and surgical care for transgender and gender diverse people. As such, gender affirming care is contingent upon DSM-5 gender dysphoria diagnosis even in cases where a person's experience does not meet diagnostic levels. Given this, it is not surprising that 15% to 33% of LGBTQ+ people report mistreatment in health care (7-9).

Proximal/Internal Experiences: The ability for some individuals to conceal their identity distinguishes LGBTQ+ people from other minoritized groups. Some consider this to be an important option that offers protection; yet concealment often comes at a considerable psychological and interpersonal cost (10). Uncertainty about when to conceal identity (for personal safety) can lead to attentional drain and further distress. One's own agreement with negative societal attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people, known as internalized stigma (also internalized homophobia or transphobia), may heighten the distress experienced by an LGBTQ+ person. Some LGBTQ+ individuals may also anticipate or fear rejection from others, leading to difficulties navigating interpersonal relationships and interactions.

Recovery From Discrimination-Based Stress and Trauma Can Be Interrelated

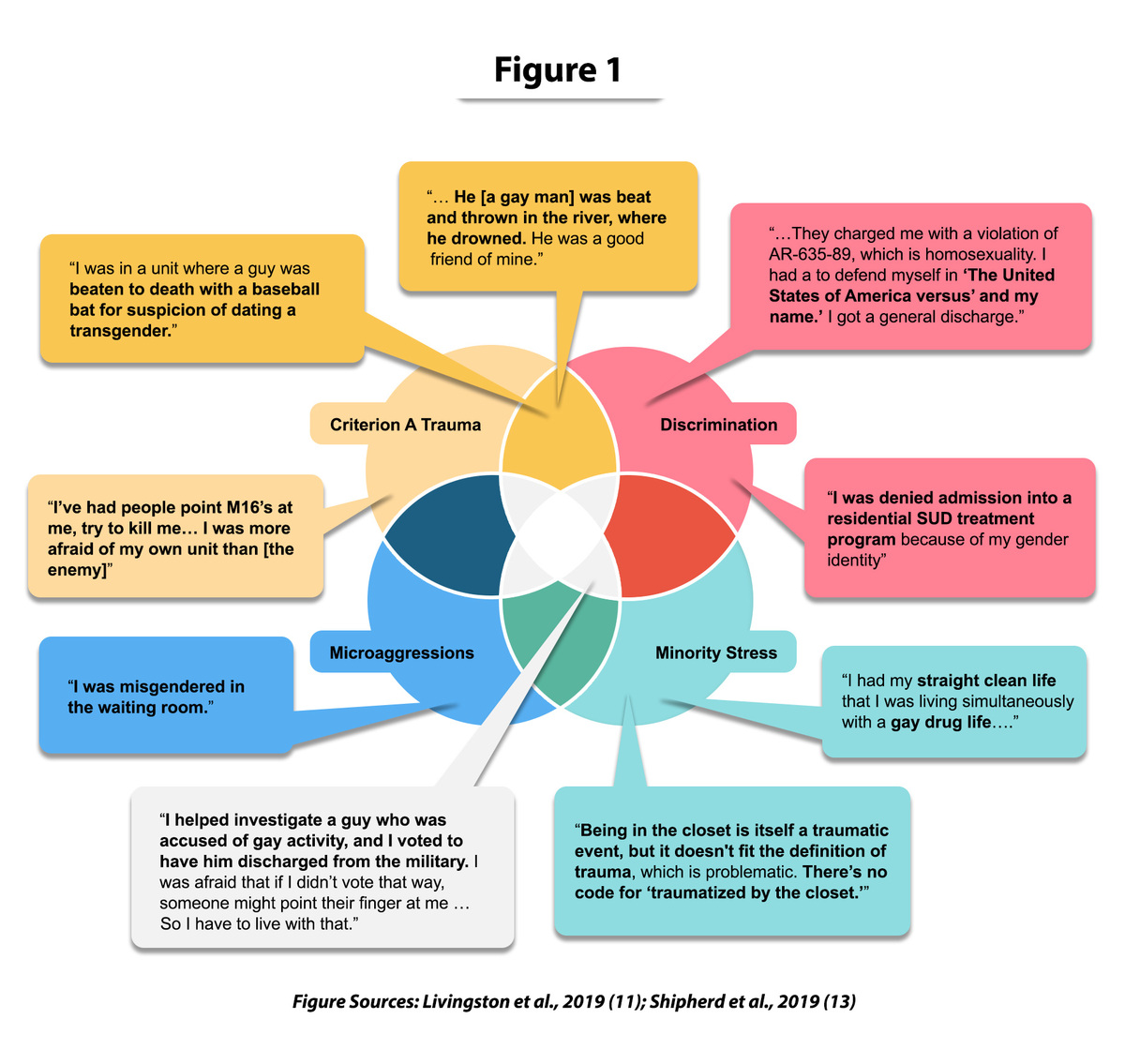

LGBTQ+ people report a range of sometimes overlapping experiences that are associated with a client's experience of PTSD symptoms (11). These include DSM-5 Criterion A traumas (events that involved actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence; 12), discrimination, microaggressions and other minority stressors. Clinicians and clients may differ in their perceptions of impact of these different experiences. First, like many people presenting to PTSD treatment, LGBTQ+ individuals may label non-Criterion A events as traumatic. Second, although clinicians tend to focus on single high impact incidents, some clients report being more bothered by persistent daily stressors (e.g., "death by a thousand cuts").

There is overlap in symptoms that result from minority stressors and PTSD symptoms from Criterion A traumas (11,13). It is also important to note that, in one study of PTSD in transgender and gender diverse adults, nearly 42% of Criterion A events represented bias (minority stress) events (14). For example, recurring and persistent thoughts and memories of past trauma can be focused on a trauma or on minority stress events. Avoidance can be related to trying not to think about the trauma or to trying to conceal one's identity. Changes to the way the person sees the world can be present in individuals with PTSD as well as those who experience minority stress. Irritability and (hyper)vigilance can be present in PTSD as well as among those who anticipate experiencing on-going discrimination and harassment. In Figure 1 (below), we highlight some of the ways these experiences overlap, as demonstrated through the words of LGBTQ+ Veterans.

Conclusion

LGBTQ+ people experience health disparities due to higher exposure to violence, the burden of additional identity-related stress, and lower access to quality treatments. The cumulative burden of various stressors leads to higher clinical distress and complexity in determining what type of exposures are most relevant to mental health. There is ongoing debate around how to think about LGBTQ+-related experiences that do not necessarily fit into the DSM-5 definition of Criterion A trauma. Some argue that LGBTQ+-related stressors be treated as equivalent to Criterion A trauma, while others suggest that minority stressors are entirely separate. A culturally informed approach is advised, where both experiences of trauma and discrimination are considered as impacting people's health and well-being. There is a need for more research to ensure that treatments are patient-centered and are inclusive of the relative contributions of these common and varied experiences among LGBTQ+ people. Learn more about Assessment and Treatment Considerations for Working With LGBTQ+ Clients With PTSD.

References

- Balsam, K. F., Rothblum, E. D., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2005). Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 477-487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477

- Flores, A. R., Langton, L., Meyer, I. H., & Romero, A. P. (2020). Victimization rates and traits of sexual and gender minorities in the United States: Results from the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017. Science Advances, 6(40), eaba6910. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba6910

- Livingston, N. A., Berke, D., Scholl, J., Ruben, M., & Shipherd, J. C. (2020a). Addressing diversity in PTSD treatment: Clinical considerations and guidance for the treatment of PTSD in LGBTQ populations. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7, 53-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00204-0

- Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., Chou, S. P., Saha, T. D., Jung, J., Zhang, H., Pickering, R. P., Ruan, W. J., Huang, B., & Grant, B. F. (2016). The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(8), 1137-1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1208-5

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460-467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

- Gruberg, S., Mahowald, L., & Halpin, J. (2020). The state of the LGBTQ community in 2020. Center for American Progress. www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/reports/2020/10/06/491052/state-lgbtq-community-2020/

- Mattocks, K. M., Kauth, M. R., Sandfort, T., Matza, A. R., Sullivan, J. C., & Shipherd, J. C. (2014). Understanding health-care needs of sexual and gender minority Veterans: How targeted research and policy can improve health. LGBT Health, 1(1), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2013.0003

- Livingston, N.A., Flentje, A., Brennan, J., Mereish, E., Reed, O., & Cochran, B. (2020b). Real-time associations between discrimination and anxious and depressed mood among sexual and gender minorities: The moderating effects of lifetime victimization and identity concealment. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(2), 132-141. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000371

- Livingston, N. A., Berke, D. B., Ruben, M. A., Matza, A. R., & Shipherd, J. C. (2019). Experiences of trauma, discrimination, microaggressions, and minority stress among trauma-exposed LGBT Veterans: Unexpected findings and unresolved service gaps. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(7), 695-703. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000464

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Shipherd, J. C., Berke, D., & Livingston, N. A. (2019). Trauma recovery in the transgender and gender diverse community: Extensions of the Minority Stress Model for treatment planning. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(4), 629-646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2019.06.001

- Shipherd, J. C., Maguen, S., Skidmore, W. C., & Abramovitz, S. M. (2011). Potentially traumatic events in a transgender sample: Frequency and associated symptoms. Traumatology, 17(2), 56-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610395614

You May Also Be Interested In

PTSD 101: Culturally Responsive Care

Understand and develop the components of a culturally responsive case formulation.

PTSD 101: Prescribing for Older Veterans with PTSD

Learn best practices for pharmacological treatment for older Veterans with PTSD.